Maps and Brochures | January 1, 2006

Restoration of a Young Coastal Douglas-fir Plantation

An illustrated summary of the Pebble Beach restoration project

ViewHow did a desire to restore plantation forests go from a “contrarian or slightly mad gambit” to an award-winning restoration program?

DL63, located within the Pebble Beach Reserve, is representative of many forested ecosystems on Galiano and throughout the Salish Sea, with a history of logging spanning a century of social, technological, and economic change.

According to Penelakut elder Florence James, Qw’xwulwis is the Penelakut name for the land now included within the Pebble Beach Reserve. James relates that it is “a place to live while resting, gathering provisions and medications, and waiting for good weather. Qw’xwulwis is the word for the action of paddling.” Indigenous people throughout the Salish Sea developed a well-documented system of forestry that provided for longhouses, canoes, tools, hats, clothing, and much more – all while preserving the ancient forests they stewarded, and in many cases even the life of the individual trees they harvested from.

This form of forestry was practiced at Qw’xwulwis for generations prior to the arrival of European settlers. According to Florence, “the respect for trees is what my grandfather told us about as children, that the tree gives its body to assist us for travel. So, a cedar tree was felled for a specific purpose and it was four to eight hundred years old. The tree was nurtured from a little sprig, limbed in a way that would prevent many knots. No single person would witness all this, as the plans were meant for future generations.”

The seizure of Indigenous territory by settlers in the 19th century introduced new approaches to forestry – approaches that were already responsible for the destruction of most of the ancient forest in Europe and much of the forested land in eastern North America at the time. At Qw’xwulwis, the initial impacts were modest, consisting of selective logging of high-value trees by hand.

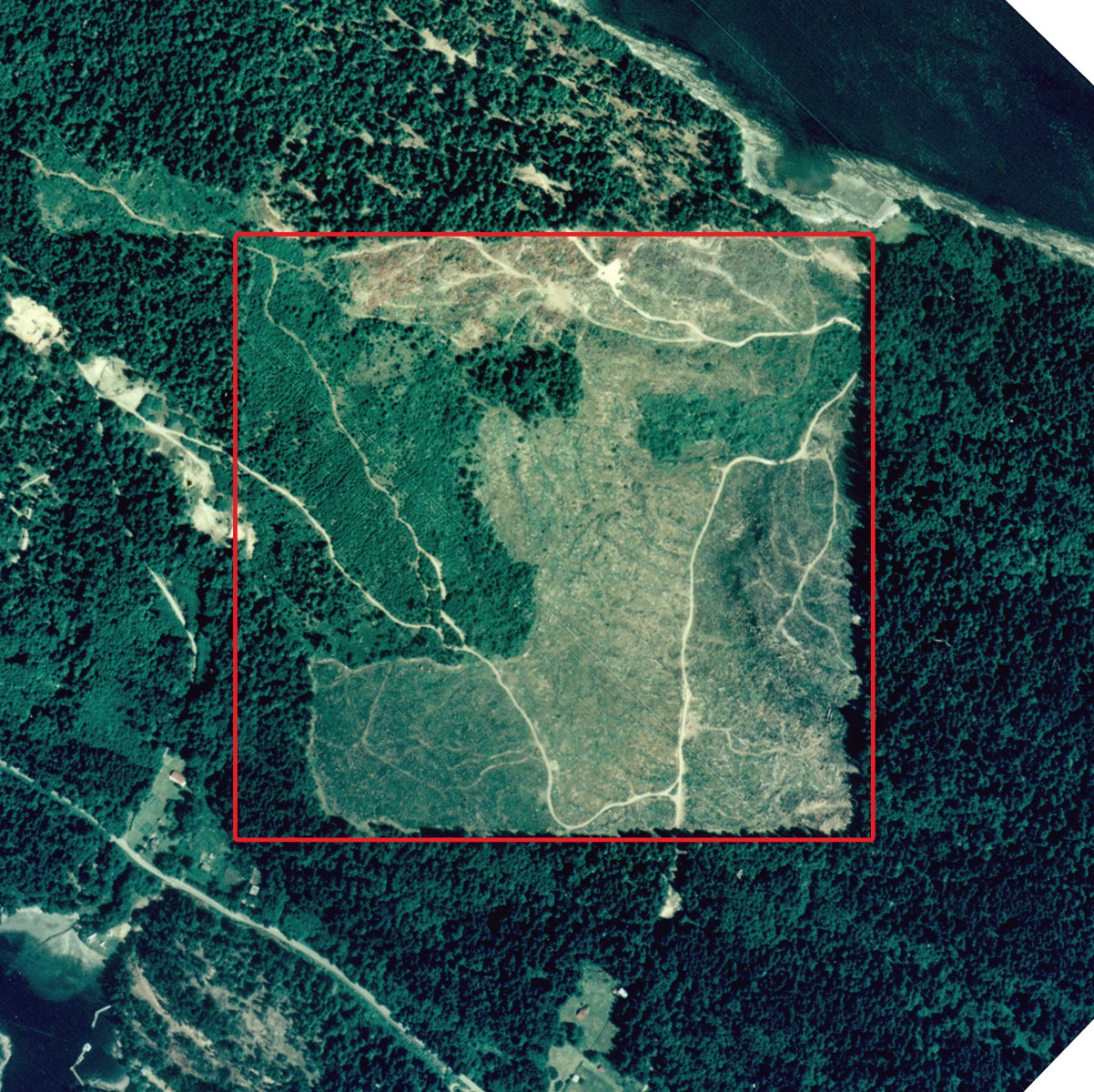

A patchy mosaic of clearings is evidence of the high-grade logging conducted with crosscut saws and steam donkeys in the early 1900’s. For several decades after this, the remaining trees were left to grow and maintain a mature forest ecosystem on the site. This first image was taken in 1932.

The first clearcut, in 1968, removed all trees from about a third of the lot. The cut was followed by an intense slash burn that penetrated beneath the forest floor through the root systems of the stumps left behind. This image was taken in 1972.

The remainder of the site was clearcut in 1978. The intensive industrial-scale treatment included the removal of every standing tree – regardless of size or species – followed by the bulldozing of top soil and slash into long linear piles called windrows. Although the site was then set ablaze, the burn failed, leaving behind the windrows and their rotting organic material. This intensive and costly treatment of the cutblock was an attempt to simplify future access to the site for planting, thinning and harvesting, as well as to control root rot. This image was taken in 1980.

The site was planted with uniform rows of genetically similar Douglas-fir seedlings selected for fast growth and size. Any other plants that naturally sprouted were quickly eliminated to ensure that the planted fir had no competition. The removal of all vegetation from the site, the devastation to the forest floor and the establishment of a uniform single-aged, single-species plantation set the forest on a trajectory where biodiversity and ecosystem processes functioned on a minimal level.

The industrial cycle was broken in 1998 when the Galiano Conservancy recognized the potential of the site to provide connectivity at the landscape scale and purchased the property for restoration. A forest restoration plan was prepared in 2002, and two years later restoration treatments were initiated to help shift the plantation’s successional trajectory towards a healthy mature forest. The goal was not the re-creation of the forest that existed prior to industrial logging, but the reestablishing of a healthier, more diverse, and resilient forest ecosystem.

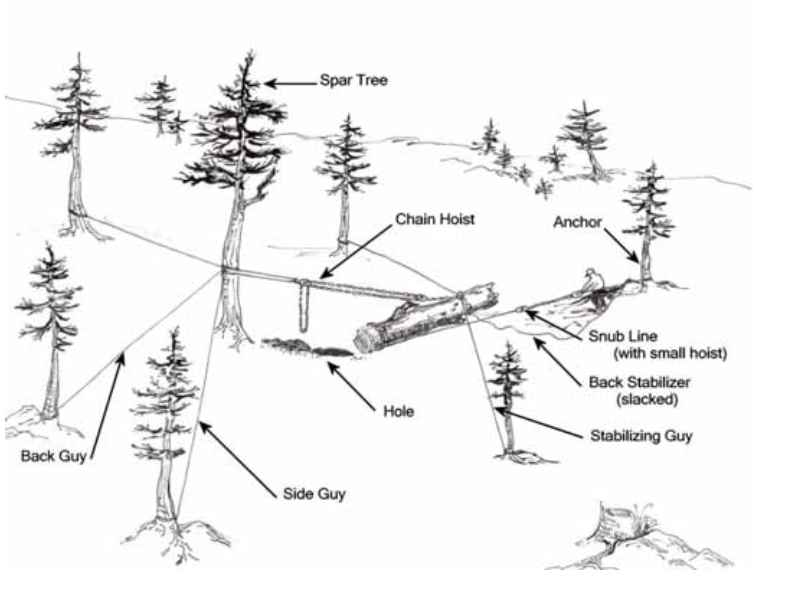

Over the course of several years, GCA staff and community members implemented a novel series of restoration treatments using only hand tools, aided by an ingenious system of hoists, chains, and pulleys devised by Ken Millard.

Using a 5-ton chain hoist for lift and a cable and pulley system for horizontal movement, rotting slash from windrows was dispersed across the barren forest floor. The organic material provides habitat for a variety of plants and wildlife, creates soil conditions conducive for the growth of mycorrhizal fungi and functions as a moisture sink during periods of summer drought. The unique, hand-powered, portable restoration system minimizes further damage to the site.

Culling plantation Douglas-fir trees created gaps in the canopy allowing more light to reach the forest floor. This promotes the growth of mosses, grasses, shrubs and other tree species. Any natural elements such as a red alder tree, a patch of salal or a small area of undisturbed soil around a stump that remain within the plantation are viewed as ‘anchors’ of diversity and provide a guide for choosing which plantation trees to keep and which to cull. Topping created small-diameter wildlife trees while opening the canopy and allowing more light to reach the forest floor. Girdling is the most efficient technique for thinning. The cambium was removed in a band around the entire circumference of trees with a specialized chisel, cutting off the transport of nutrients to the roots. Pulling trees over mimicked natural windthrow, creating a pit and mound feature on the previously scraped and flattened forest floor. The chain hoist in series with a number of chains, pulleys and cables easily brings the trees down by hand.

Using a modification of the cable system, large, intact pieces of slash were stood up as wildlife trees, creating forest structures that would otherwise take centuries to form.

Within just a couple of years of the treatments, the plantation had already responded with an increase in species richness and biomass. The moss layer was the first to respond to the increase in light resulting from thinning treatments. The grasses and herbs followed quickly, along with a flourish of shoots branching off of red alder stems. Salal (Gaultheria shallon), ocean spray (Holodiscus discolour), and other shrubby species arrived slowly over time.

A number of students have designed studies around the Pebble Beach restoration over the years. A soil study performed shortly after the treatments demonstrated that by 2005, soil nitrogen and phosphorus levels in the treated areas were closer to those of the nearby mature forest at DL 60 than they were in the control plots in the plantation forest. A second study performed several years later, confirmed that the restoration had successfully increased the biodiversity and stand structure heterogeneity of the treated areas, as well as having no deleterious impacts on soil carbon and nitrogen levels. Most recently, a 2017 study found that the treated plots showed improved measures of biological and structural diversity (Hohendorf, 2018). However, the same study was unable to directly link these improvements to the restoration treatments and found that some of these differences were not statistically significant (ibid.). The author suggested that the results may have been more significant had the initial treatments been more intensive, and if there had been follow-up treatments performed in the intervening years.

Most recently, a 2015 study found that the treated plots showed improved measures of biological and structural diversity. However, the same study was unable to directly link these improvements to the restoration treatments and found that some of these differences were not statistically significant. The author suggested that the results may have been more significant had the initial treatments been more intensive, and if there had been follow-up treatments performed in the intervening years.

These studies demonstrate the importance of long-term monitoring for generating knowledge and helping us design better restoration projects in the future. They also suggest that future restoration treatments in the Pebble Beach Reserve could go beyond the original treatments in terms of scale and intensity without causing significant ecological harm, and yield greater benefits. The results are promising, and the insights gleaned can be applied elsewhere on Galiano and throughout the Salish Sea.

Over the past two decades, thousands of students of all ages have visited, learned about, and participated in the restoration of the Pebble Beach Reserve. Programs have ranged from an intensive week-long Forest Ecology workshop to day programs for regional schoolchildren. The Galiano Conservancy’s education team regularly offers the award-winning Coastal Forests of Pebble Beach program to school groups, teaching young people about the impacts of industrial forestry, how to recognize healthy ecosystems, and the power of ecological restoration to heal our ecosystems and ourselves.

You can visit the Pebble Beach Reserve and take a self-guided tour of the restoration areas on an interpretive trail with the help of the DL63 Forest Restoration Brochure, which is available at the McCoskrie trailhead. Today, the Galiano Conservancy continues to use Ken Millard’s one-of-a-kind chain hoist and pulley system to pull down trees in the plantation forests of the Pebble Beach Reserve, only this time, it’s schoolchildren doing the pulling. If a tree falls in the middle of the woods – whether or not anyone hears it – you can bet that it’s contributing to the overall complexity, health, and resilience of the forest.

Explore the following resources to learn more about the restoration in the Pebble Beach Reserve.

An illustrated summary of the Pebble Beach restoration project

ViewReport from UVic’s ES 471 Class of 2021.

ViewMilestone Timeline | Reflections from the Education Department | Sustainable Living | Species At Risk in Your Backyard | Restoration, Learning, and Memory

ViewForest Restoration | Herbal Workshop | Solar Energy | Elder Relations

ViewHohendorf, 2015 – Masters Thesis

ViewHarrop-Archibald, 2007 – Masters Thesis

ViewKoele, 2005 – Proceedings of the 2005 SER-BC Annual Conference

View“We Receive Our Breath from the Trees” | Ecocultural Restoration | Restoring Forests and Culture in S. Korea | Healthy Forests, Healthy Soil | The Golden Spruce | Where do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going | The Garden of Memory

ViewScholz et al., 2004 – 16th Int’l Conference of the Society for Ecological Restoration

ViewErickson, 2003 – Georgia Basin / Puget Sound Research Conference

ViewL.I.F.E. Comes to the Pebble Beach Reserve | UK’s National Trust |

“A Sense of Place” | Reviews | Letters | For every bird today … there must have been a thousand

Notifications