Caring for all our Relatives with ṮEṮÁĆES Climate Action

When I arrive at Spanish Hills to pick up -Sha aal tin aat- Karen and -Thaythits- Richard Charlie from an early boat trip over from Penelakut Island, they’re already waiting on the dock. They’re looking out over the smooth water back towards Penelakut and the snow-clad mountains beyond, pointing out the sea lions and even a distant humpback whale. “There used to be so much more,” they tell me. In the distance, we count a half-dozen massive oil tankers idling in the channel around Penelakut and the north end of Galiano. They’re a stark, omnipresent reminder that, whatever has been lost up to this point, all that remains could be lost in just an instant.

We arrive at the Millard Learning Centre just in time to plug the car in and start a fire in the classroom before the big yellow school bus arrives. Out pour 25 youth from across the Southern Gulf Islands, including 10 young people from the three W̱SÁNEĆ First Nations. They are accompanied by elder -SELILIYE- Belinda Claxton, W̱SÁNEĆ Language revitalization coordinator Tye Swallow, and Paul Petrie – the program coordinator for the ṮEṮÁĆES Climate Action project.

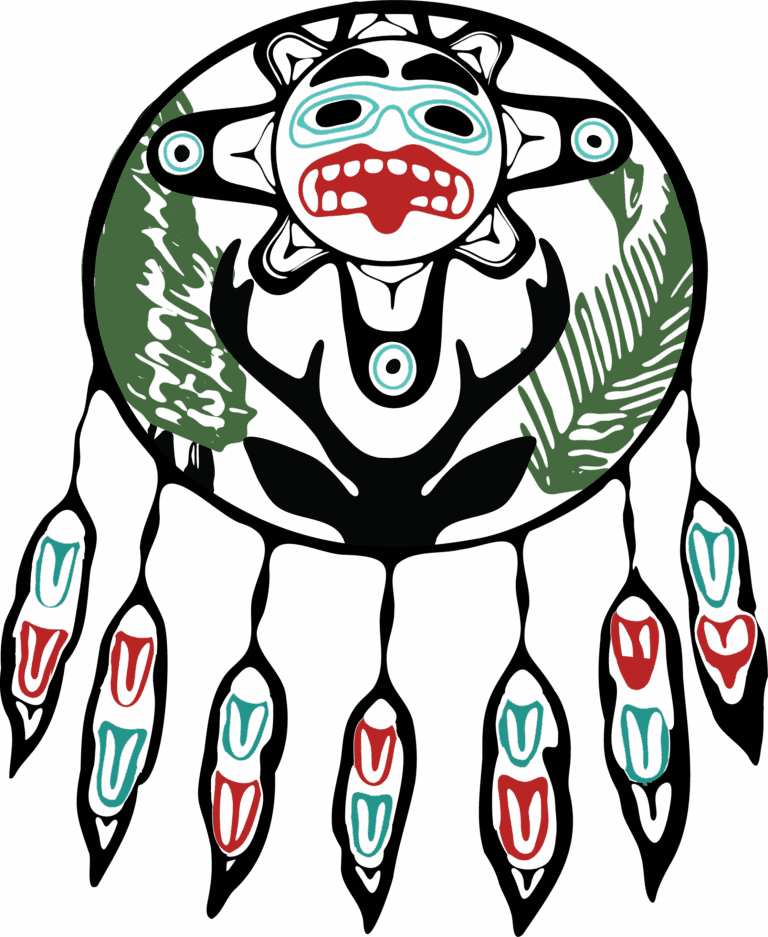

According to -PENÁC- David Underwood:

“ṮEṮÁĆES is the W̱SÁNEĆ name for island, or islands. Roughly translated, it means relatives of the deep, which refers to the story of how the islands got to be. It is said that long ago XÁLS (the creator) came to W̱SÁNEĆ to change many things about the world. He came to the territory aboard a canoe at the area known to W̱SÁNEĆ as ȾIX̱EṈ – the Cordova Spit at Saanichton Bay. XÁLS came ashore. He then walked toward the westside of the point, where he cast a black stone into the horizon, followed by another black stone, which became ȽÁUWELṈEW̱ (John Dean park, Mt. Newton). XÁLS had with him a basket, that he loaded with more black stones and then walked toward ȽÁUWELṈEW̱ . Several people had witnessed the sacred spectacle and in their curiosity followed XÁLS to the mountain. Atop the mountain XÁLS proceeded to cast more black stones, which then made the mountains. When he ran out of stones he turned toward the people who had followed him to the mountain and began to grab people who were of the greatest virtue. He cast them out into the ocean and told each of them, “QEN,T TŦEN SĆÁLEĆE” (look after your relatives). They then rooted themselves deep into the ocean, becoming the islands. He was done casting people to the water and turned to those who had remained with him on the mountain and told them, “I, QEN,T SE SW̱ TŦEN SĆÁLEĆE” (And you will look after your relatives)”, and gestured to the ṮEṮÁĆES.”

The ṮEṮÁĆES Climate Action project was created by the W̱SÁNEĆ Leadership Council and the Southern Gulf Islands Community Resource Centre to look after these relatives of the deep: to reconnect W̱SÁNEĆ and non-indigenous youth in the Southern Gulf Islands – the ṮEṮÁĆES – to the land and water, to share traditional knowledge, and to explore decolonizing approaches to climate action. The pilot phase of this project has been three 5-day intensive courses getting out on the land, learning alongside elders, and digging deep into solutions. The students have already been out on the land on st̕ey̕əs – Pender Island, and in the coming days will visit Saturna and Mayne Islands as well.

But this day, on Galiano, is unique, in that Galiano Island is the unceded traditional territory of the Penelakut and of Hul’qumi’num speaking peoples, as well as the ceded territory of the Tsawwassen First Nation. Karen and Richard formally welcome the group to Penelakut territory, and we sit down in the classroom to some wildcrafted herbal tea and stories from her childhood and adolescence. Throughout, she weaves information on the uses of medicinal plants, the right to harvest from the territory, and the changes she’s experienced in her lifetime. The memories from her years in residential school are particularly difficult to bear witness to, but the youth are attentive throughout, and in the end, she reminds us: “These are my experiences to carry. Don’t take them on yourselves.” Before long, Richard and Karen are cracking jokes, leaving us in fits of laughter. In a highlight of the day, Belinda and Karen compare phrases and plant names in SENĆOŦEN and Hul’qumi’num – they sound so similar, but with differences that reveal unique aspects of the ancient cultures from which they arise.

As the sun rises high in the sky, we venture outside into the Nuts’a’maat Forage Forest, where several years prior, GCA staff, Penelakut elders (including Karen and Richard), and children from the Penelakut Island School planted hundreds of useful edible and medicinal native species. Those plants are now well established and on their way to producing food and medicines for climate changing times, and the group samples some tasty nodding onion and miner’s lettuce greens from a series of berms planted with native herbs and wildflowers. Vibrant shoots of camas poke up between the greens throughout the berms, promising harvests of edible roots in future years. As we walk, Karen and I share what we know about the plants and their uses in this diverse, regenerating ‘forest’ – a unique eco-cultural restoration project in our region. We finish the morning by planting some native wildflowers – farewell-to-spring, tomcat clover, spring gold, and q’uxmin, an important medicinal and ceremonial species that Karen had introduced to the group earlier in the classroom.

Lunch consists, in part, of smoothies produced by pedal power using the GCA’s custom smoothie bikes. In the afternoon, we walk together up the hill to the Program Centre, where a large solar array and miniature windmill produce renewable energy for the Millard Learning Centre and the electric vehicle chargers. Tom Mommsen and the Education Team go deep on how the islands could become solar and wind powerhouses. Between renewable energy, indigenous foods, ecological restoration, traditional knowledge, and a dedicated group of elders and young climate activists from across the islands, we’ve brought together a powerful set of responses to the climate crisis. Even just within our community, we have what we need to act.

As the GCA’s yellow school bus transports the group on to the next stage of their journey, I head back up to the Spanish Hills dock with Karen and Richard. “This was a good day,” Karen tells me, and I feel the same way. At times, the climate crisis can feel completely overwhelming, but the community that we are building together is resilient. There is still much work left to do, and the tankers lingering around Penelakut Island are still there to greet us as we return to the dock. But waving to Karen and Richard as the water taxi takes them back across the channel, I can’t help but feel a little bit hopeful.

For more information on the project, check out: https://www.sgicommunityresources.ca/climate-action-project/