Student Reports | September 21, 2022

Chrystal Creek Wetland Design Project

Report from UVic’s ES 471 Class of 2022.

ViewDistrict Lot 57, which would become the Millard Learning Centre, was pre-empted in the late 1800s by European settlers. By the 1930s, when the first aerial photos were taken, a large homestead had been established and fields had been cleared for agriculture and pasture.

By 2011, large swathes of the property had been logged, and several areas had been ditched, drained, and concerted to garden and pasture land. Dilapidated structures and the accumulated detritus of over a century of settler use and occupation littered the land.

When the Galiano Conservancy acquired the property in 2012, we inherited a complicated network of old logging roads, ditches, fence-lines, and structures cutting across the Chrystal Creek watershed. The landscape had been cleared and simplified, with a dominant cover of aggressive introduced agronomic grasses and weeds. The original creeks had been diverted into ditches, and rainfall was quickly siphoned off the land and down into Chrystal cove.

During intense storms, rainfall would overwhelm the ditches and spill out onto the roads, leading to erosion and flooding. Areas that would flood in the wintertime would become bone-dry during the summer droughts, supporting little to no native vegetation.

Despite the degraded state of ecosystems throughout the Chrystal Creek watershed, there were signs that recovery is always a possibility. Poorly-drained, flooded areas provided clues as to where historical wetland ecosystems may have occurred prior to being converted for agriculture. Lone western redcedar | X’pey (Thuja plicata) trees persisted on raised mounds of woody debris.

The first step was to demolish dilapidated structures and clear away garbage and and other debris that littered the lower watershed. Wherever possible, woody debris from structures would be re-incorporated into the soil during restoration treatments. Useful items were re-used, given away, or recycled. This process took several years and is still ongoing as additional restoration treatments reveal more layers of garbage.

To restore wetland ecosystems, we knew we needed to put together a team of experts and knowledge holders. Wetland restoration expert Robin Annschild (of Rewilding Water & Earth Inc.) joined the project early, along with biologist and former GCA Executive Director Keith Erickson. Penelakut Elders Karen and Richard Charlie graciously provide their insights, and excavator operator Stuart Callison provides a steady hand behind the wheel to artfully and expertly apply restoration treatments.

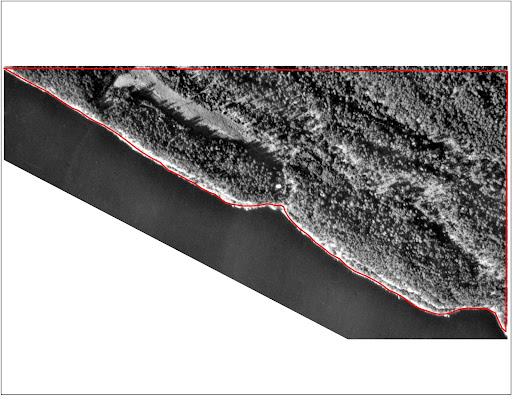

Prior to any restoration treatments, GCA staff, interns, and student volunteers perform detailed site assessments. Roads, ditches, and ecological communities across the watershed are mapped in order to inform restoration planning.

To restore degraded wetland ecosystems, we needed large amounts of coarse woody debris (CWD) to create habitat, retain moisture, cycle nutrients, build soils, and provide seed germination sites. We were able to generate this material by thinning an adjacent plantation monoculture of Douglas-fir | Ts’sey’ (Pseudtotsuga menziesii) trees using Ken Millard’s purpose-built chain hoist system.

Most of the heavy lifting is performed by an excavator. Compact soils are loosened, roads and ditches are removed, coarse woody debris is distributed, and wetland pools are excavated.

When the dust clears and the rains begin to fall, the wetland pools quickly fill and immediately provide habitat for a wide range of species. Amphibians, including the Blue-listed northern red-legged frog (Rana aurora), begin breeding in wetland pools within six months.

Post-agricultural soils hold large seed banks of introduced species. To ensure that native vegetation eventually becomes established in restored areas, we employ a combination of planted nursery stock, live-stakes, and seeding of native species. New plantings and restored sites are protected from browsing through fencing.

Hundreds of students, community volunteers, and interns have contributed to restoring the Chrystal Creek watershed. Volunteers groups and classes from UVic, UBC, SFU, BCIT, and the BCWF have all participated in the project. Volunteers provide expertise, enthusiasm, and thousands of hours of volunteer labour. Dozens of students have produced reports to inform ongoing restoration, monitoring, and interpretation activities.

Once a section of the watershed has been restored, ongoing monitoring and management is required to ensure that the restoration is successful. Aggressive introduced species must be controlled, and the results of different treatments must be assessed to determine their efficacy. Wetland ecosystems become instant habitat, but native forests take much longer to regenerate. We view this project as a generational commitment to the recovery of a watershed.

One of our favorite activities is using our hydrophone to listen for the breeding calls of one of our target species, the northern red-legged frog. So far, we have recorded calls and observed egg masses on an annual basis in several of the largest wetlands we have built.

As the creek and wetland system evolves, braided channels develop as the water finds new paths down to the ocean. To prevent erosion from occurring during this natural process of creek development, we employ a suite of practices known as ‘soil bioengineering’, which rely on the incredible regenerative capacity of willow, cottonwood, and dogwood branches. Simple combinations of rock, mud, and live-stakes taken from these species do an incredible job of holding soil and spreading water. In this photo, Canada Conservation Core interns have successfully installed three “beaver dam analogues” (or BDAs) to slow and spread flows in a newly formed stream channel.

We celebrated the completion of primary restoration treatments across 12 ha of the Chrystal Creek watershed in 2024. Natural hydrology has now been restored from ridgeline to shoreline! We will continue to host volunteer groups, events, and field courses in the watershed as it grows and evolves over time. There is always more work to do to ensure that the vision we have for the watershed becomes a reality!

Explore the following resources to learn more about the restoration in the Chrystal Creek watershed.

Report from UVic’s ES 471 Class of 2022.

ViewCameron, 2021 – ER 312B, UVic

ViewReport from UVic’s ES 471 Class of 2021

ViewReport from UVic’s ES 471 Class of 2021.

ViewDewar, 2021 – RNS Capstone Project

ViewReport from UVic’s ES 471 Class of 2020.

ViewReport from UVic’s ES 471 Class of 2020.

ViewReport from UVic’s ER 412 Class of 2018.

ViewNotifications